Hurricane Ivan stripped my mother of her home, car, and job in one fell swoop. For someone already struggling with mental health, this experience broke her. Mom sheltered in her apartment, trapped by a huge old-growth Oak Tree that fell through her roof. It took two days for help to come.

Ivan ransacked Pensacola. Bridges were destroyed, roads were flooded, and homes and businesses stood gutted. People from outside of the Gulf Coast asked that same old question: “Why didn’t people evacuate?”

I can’t speak for everyone who stayed, but I can speak for my mother and those like her. She took care of an elderly patient on oxygen who was bedridden. Moving Margie, her patient, was impossible. At the same time, Mom’s car was less than road-trip worthy, and her bank account couldn’t withstand the gas and lodging it would have taken to leave. All the things added up to sheltering in place.

Other people stayed for similar reasons. Disabilities. Poverty. Lack of transportation. Stubbornness. A pack of farm animals that would have made it next to impossible to leave. People build significant lives in one place, and leaving in the chance that a hurricane hits their home seems like a gamble; sometimes, that doesn’t make sense. There’s also the economic side- entire cities don’t shut down because a storm may hit. Companies don’t shut down. Emergency operations still run, and the businesses that serve those operations are still available. Some may be surprised to hear that a gas station has to stay open to fuel vehicles, and the people behind the register there cannot evacuate. People HAVE to stay. The state cannot shut down.

In any case, many people remained, and the trauma that they endured was no joke.

I relay this story because Hurricane Ian just barreled through my serene second hometown, Englewood, FL. I have family and dear friends there who withstood similar trauma as my mother in Ivan. The town endured mass destruction—when I look at pictures and video, my heart sinks. I realize I haven’t posted quite yet, even though I have started this piece about a hundred times.

Southwest Florida is indescribably special. We grew up swimming in crystal clear Gulf water. We learned about manatees and alligators up close and personal. Cougars visited us from rescues at our school assemblies, and we took field trips to Thomas Edison and Henry Ford’s Winter Estates in Ft. Myers, which is now temporarily closed because of the hurricane. We didn’t have metal detectors at our school, and there wasn’t much to do other than go to the beach and hang out with our friends—at the beach.

Englewood was always and will always be the picture-perfect beach for me. It was the first beach I ever visited and remains the bar against which every beach is measured, and suffers. We ran to Englewood after moments for which I have no words, and it was our solace. We attended Sunrise Service on Englewood Beach Service to affirm our Faith.

I am in Cincinnati and watching as my friends and family rebuild. I hope they address their trauma with as much care and urgency as they are the treasures of our beautiful SW FL towns and beaches. Speaking from experience, they can break a person.

If you’d like to help give, please visit this link.

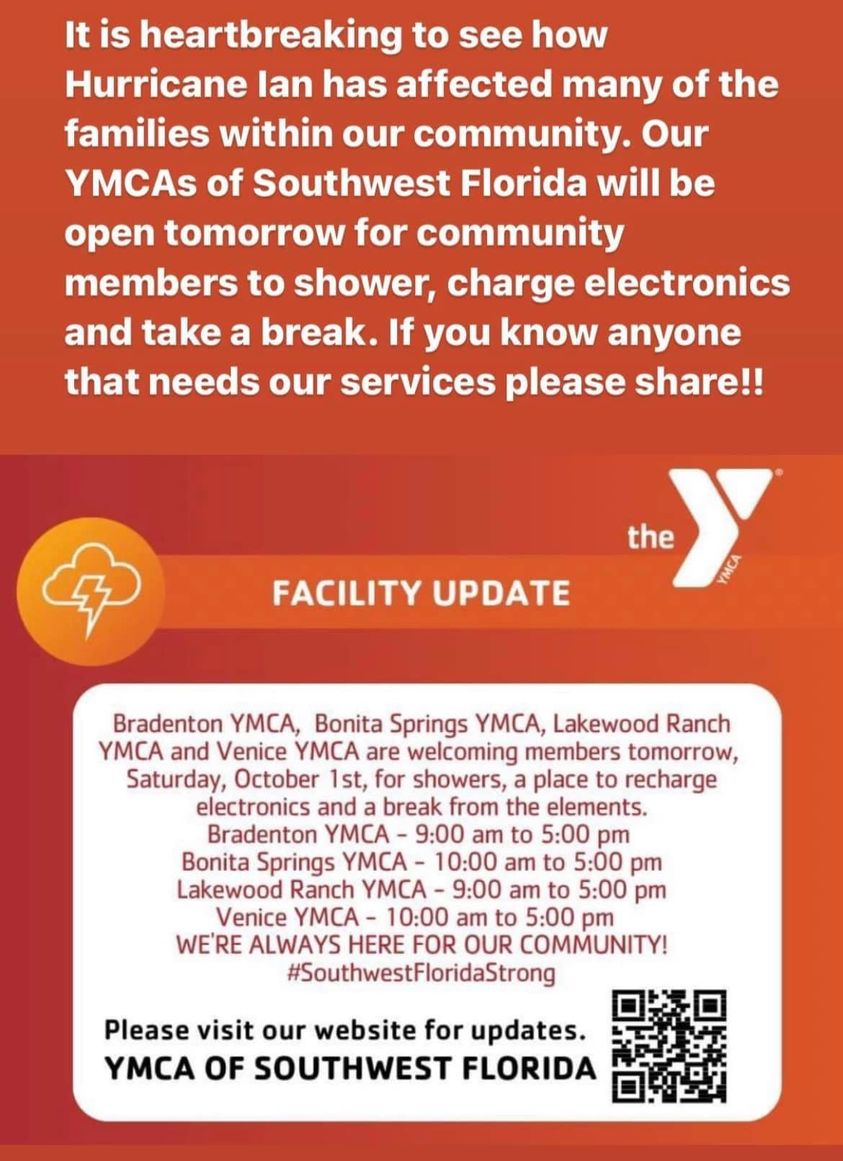

The collective consciousness of a disaster-stricken community is what pulls them back up, and I am not skeptical about the Gulf Coast. Instead of posting devastation pictures, which we have ALL seen, here are some beautiful images of resources, working together, and help.